Introduction: When the Tide Seems Too High

As I write this in early June 2025, the S&P 500 sits at a trailing P/E ratio of approximately 28, well above its 20-year average of 16. The Shiller P/E (CAPE) ratio stands at 36.5 levels, which has historically preceded significant market corrections ( and I know I know the more we rely on these statistics as a guide, the less effective they become, anyway). The current earnings yield of roughly 3.5% compares unfavourably to the 10-year Treasury yield, while the index's dividend yield hovers near historic lows at approximately 1.3% and landmark highs of a net margin of 12.7%. Perhaps most striking is the concentration: the top ten companies in the S&P 500 now comprise nearly 40% of the index, a level of concentration that rivals the dot-com peak (20-30% concentration for top 10 companies). These metrics alone don't predict when or if a correction comes, but they paint a picture of a market deviated far above its historical norms.

The S&P 500 has generated an annualized total return of 16% over the past five years, compared with a 30-year annual average of 10%. Such an extraordinary performance naturally raises questions about sustainability and valuation. The current market environment bears many hallmarks that resonate with previous market tops. They say you can't time the market, but sometimes you can feel the ripples before a big wave crashes.

Background: The Evolution of an Investor

When I first began managing my money seriously, I suffered a significant loss due to overconfidence and a profound misunderstanding of my own gaps in knowledge and weakness towards biases. That painful education led me to reform my approach systematically, create checks and balances, improve my research methodology, and develop a more rigorous valuation framework. The intellectual foundation for this transformation came from studying investors bred from the school of thinking established by Ben Graham and Phil Fisher. Their emphasis on understanding what you own, rather than simply following market momentum, became central to my philosophy.

One of my biggest concerns during those early money management years was the digitization of money and what I call the "casino chip effect." When you separate the imagery and connection with physical money, it becomes harder for the human brain to gauge the actual value of their action (track real gains and losses, or scale of their risks). Fearing I might lose that essential connection with the reality of my capital, I deliberately separated a large portion of my portfolio into index funds and bonds. This decision protects against my mistakes and limits the tuition I am paying for my market education (paying in losses). In hindsight, this decision proved remarkably fortunate. The index funds provided spectacular returns over the past five years and served as an excellent hedge against my early stupidity as an investor.

The Munger Models: Simple Ideas Taken Seriously

This decision of owning the majority of my funds in an index fund and high-grade bonds might have made a lot of sense back then, but today, realizing that most of my funds are in a “black-box” (A "black box" refers to a system whose internal workings are unknown or disregarded, in contrast to a "white box" where the internal mechanisms are fully transparent and understood) makes me rather uncomfortable. Charlie Munger's wisdom offers two models that have helped me crystallize this discomfort. The first is his admonition to "take a simple idea and take it seriously." The simple idea here is to really understand what you own, not “subcontracting investing to a black box” and expecting things to go well. Yes, even with the S&P 500's historical outperformance against most active managers, a fundamental truth remains: you must understand what you own. The current market-weighted S&P is heavily concentrated, with just ten names driving the lion's share of the past decade's returns. This concentration is particularly concerning given elevated valuations, historically high profit margins, and a business cycle where American equities have enjoyed significant tailwinds. The risk here is that such narrow leadership, coupled with stretched valuations, could lead to a domino effect within the index during any significant market panic. The comparison model is the second model in Munger’s toolkit that helps me think through owning an index fund. In this example, every day you own an index, you own it over something else, meaning you need to constantly have something to evaluate what you would rather own, sort of like a yardstick. When I evaluate an investment opportunity today and compare it to holding the index, I feel far more comfortable investing a substantial portion of my wealth in companies where I understand the business fundamentals, risks, and profit drivers, earning power and transperent valuations than an index whos main argument for being owned is not valuation but the notion that that the past decades returns is believed to continue and that over a long period of time the index fund has outperformed most active trading inventors.

The Indexing Paradox: When the Solution Becomes the Problem

The past year has really made me ponder whether, at this time, I should own index funds. When I think deeply about how indexing and dollar-cost averaging have been marketed, constantly putting money into a market-capitalized average to smooth returns over time, two red flags emerge. The first is historical precedent. One could argue that the current advice of constantly putting money into a market-capitalized average has become as systematized as the "Nifty Fifty" was in the 1960s-70s. During that era, the top 50 companies were seen as a "one decision" investment, with the phrase "you can't get fired for buying IBM." These were considered the ultimate blue-chip, buy-and-hold forever stocks. However, in the correction of the 1970s, many of these names suffered dramatically, with some components dropping 91% from their peaks. Although in hindsight, over 25 years, many of these companies as a group still performed well, it's a risk that should be deeply considered. The parallels to today's concentrated index investing are striking. We've simply replaced "you can't get fired for buying IBM" with "you can't get fired for buying the S&P 500." The second concern addresses a more fundamental question: What happens if the majority of global cash flow becomes indexed? Fund manager Joel Greenblatt provides what I believe is the best answer to this question. He states that if you have cash and you keep buying a basket without differentiating what's in the basket, sooner or later, you will find bargains available when purchasing certain items separately. If the S&P 500 continues the pattern of the last few decades and keeps growing in concentration, this reality will become an increasing advantage for those willing to do the work of stock picking. As more capital flows passively into the most prominent names regardless of price, the opportunities for active investors to find mispriced securities, both overvalued index components and undervalued non-index companies, should increase. This factor creates an interesting paradox: the more successful indexing becomes as a strategy, the more it may undermine its own effectiveness by creating the very market inefficiencies that skilled active managers can exploit.

The Pattern of Concern: Eight Years of Warnings

As I've been pondering my index fund position, I've been rereading and discovering more investment letters from fund managers I follow. A striking pattern emerges: serious concerns about S&P 500 valuations began appearing around 2017. If you had taken this advice literally in 2017, you would have missed one of the best historic index runs in market history. However, as you examine the underlying reasons, outlier valuations, risk of falling margins, and the exhaustion of many tailwinds that propelled businesses to grow at extreme rates, the concerns appear prescient rather than premature. Many of the factors that drove unprecedented growth (population boom, economic investment in globalization, supply chain efficiencies) are now poised to face growing pressures. Moreover, the rule of large numbers is making it increasingly difficult for the big names that overpopulate the index to continue growing at unrealistic rates.

Among the many excellent investment letters I've encountered over the past eight years, those from Semper Augustus Investment Group LLC stand out, particularly their 2021 and 2024 annual dispatches. While I could attempt to recompile the warning signs and valuation statistics surrounding the index, more experienced fund managers have already done a far superior job than I ever could. Therefore, rather than repeating what Fund General Partner Christopher P. Bloomstran accomplishes with unparalleled rigour in his letters, I'd prefer to piggyback on his work and refer you directly to his insights. (You can easily find his annual letters online; they are renowned as some of the longest and most meticulously detailed in the industry—this year's iteration, for example, was 166 pages of pure wisdom.) His entire body of work is brilliant, but for our purposes, the specific section that dissects index performance around secular peaks (like the dot-com era) and outlines the different assumptions (simulated returns) required for the next decade to achieve excellent returns (absent hyperinflation) is particularly relevant, beginning on pages 64-94. I highly suggest those interested glance at the letter for its extensive information. Its highlights focus on current valuations, margin rates, the underlying assumptions, and the compelling reality that it will be exceptionally difficult for the S&P to duplicate the last five years' returns in the next five.

If you are pressed for time, and need to take away only the most important points from the letter, I've highlighted five crucial facts below:

“Numerous surveys of both retail and professional investors in late 1999 and early 2000 concluded stocks would compound over the coming decade at annualized rates of return ranging from 16% to 20%. Below is a chart from an academic paper by two Harvard researchers, Greenwood and Schleifer, who examined six surveys of investor expectations. While a bit busy, Gallup surveys of investors between 1995 and 2011 revealed 16% expectations of both expected and minimum acceptable returns at the taking of their 1999 poll. That was the peak. The S&P 500 had compounded at a high-teens annual rate for the prior 17 years. Of course, their expectations were ahead of the coming reality. The index posted a total return loss over the next ten years and returned 7.7% over a quarter century. By the market secular low in 2002, after the index had declined 49% in price, future expectations were for a 6% annual return. Investing in the rear-view mirror.”

“The two largest return drivers over the decade were expansion in the P/E multiple from 13.0x to 22.9x and in the profit margin from 9.2% to 13.3%. These two factors contributed the majority of the return earned by the index. Dollar sales compounded by 3.4%, dividends added 2.3% and a net reduction in the share count added 0.7% to return.”

“Decade-long returns only exceeded 15% on four occasions. The late 1920s and late 1990s are examples. Washouts are equally telling. There are precisely five yearly intervals when trailing ten-year returns were zero or negative. When? 1937 (0.0%), 1938 (-0.9%) and 1939 (-0.1%), which followed 1929’s stock market bubble and the Great Depression when stocks declined 89% peak to trough and only again in 2008 (-1.4%) and 2009 (-1.0%), the Global Financial Crisis which followed the tech bubble ten years prior. The S&P 500 troughed 57% below its 2000 peak nine years later. That’s despite eight years of economic growth in the interim. The pattern is simple: Historically low 10-year returns tend to follow historically high valuation levels.”

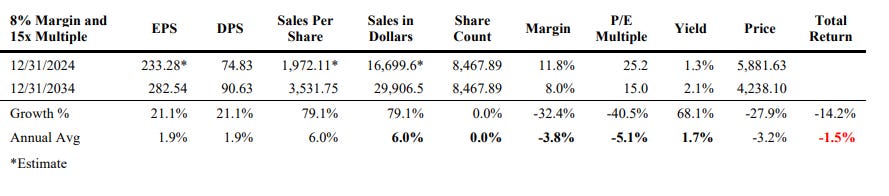

Multiple simulations exist, but I will share the simple average return simulation. For more, please look at the letter:

I'll end this tribute with my favourite quote from the letter (also a reference to the Magnificent Seven), found on page 77: "I had a vivid dream of the number seven, just a giant seven... and when I woke up, it was 7:00... so I get up and decide to go to the track, because I like to play the ponies... and I get a cab, and the cab pulls up, and it’s number seven... so I get to the track and I ask what I owe, and it was $7.77... I go in through gate seven, and the only booth open is the 7th. I look at the board and in the 7th race there’s a horse named Lucky Number 7, and his odds are 77/1. So, I put $700 on him... and believe it not... he came in 7th.” – Norm MacDonald.

A Personal Decision, Not Universal Advice

For now, I'm cashing out of my market-weighted index funds. Let me be clear: I'm not suggesting this is a poor choice for everyone. For the average investor who prioritizes simplicity, consistently invests, and is comfortable with the likelihood of lower returns in the coming decade, or even seeks a hedge against hyperinflation through rising asset prices, index funds can be perfectly suitable. My conviction, however, stems from a readiness to take full responsibility for my investment outcomes, fueled by an aspiration to outperform the index over the long term significantly. Without hyperinflation, its future performance will fall well short of historical averages. This decision also reflects my comfort in investing in a limited scope of companies I have a greater understanding of, rather than pushing a portion of my wealth into concentrated index funds built on the assumption of a perpetually rosy world and valued as if multiples won't contract.

Conclusion: Knowing What You Own

The market may continue to rise higher from these levels. According to the letters I read, these warning signs started as early as 2017 and have only gotten more and more severe. With its extreme valuations, historic concentration, and speculative undertones, today's market environment feels like one of those periods when understanding what you own matters more than riding the momentum. I know many will repute what I say and tell me I can't time the market, but look at the greatest investors many are echoing concerns, Buffett for instance also exited the market in 1969 when he couldn't find bargains as well as in the late 90s (funny enough, Berkshire has a huge cash position at the moment). I'm not trying to time the market perfectly. I'm choosing to own things I understand rather than hoping that unprecedented market concentration and valuations will continue to work in my favour. As Benjamin Graham once wrote, the market is a voting machine in the short run, but in the long run it's a weighing machine. After years of voting based on momentum and multiple expansion, I suspect we may be entering a period where the weighing will matter more. The ripples are getting larger. I prefer to swim in waters I know well when a big wave comes.

I will end this with a fun story whose origin I can’t quite find: "I had a vivid dream last night. I dreamed that I died and went to heaven, where I was reunited with all the great investors who came before me... Ben Graham was there, as were Phil Fisher, Charlie Munger, and Walter Schloss. Even Jesse Livermore had made it in. I asked Ben Graham what the secret was to making money in this market environment. He leaned over and whispered in my ear, 'The same as it's always been... buy a dollar's worth of assets for fifty cents.' Then I woke up."

This memo reflects my personal investment decision based on my risk tolerance, time horizon, and understanding of individual businesses. It should not be construed as investment advice for others.

Really enjoyed this one, Dan, learned a lot from the casino chip idea and the Munger models. Super interesting stuff. Keep up the great work!